The Young Ones

Oh, all right then . . .

It’s just odd trying to write about The Young Ones. I find it very difficult. It’s almost too big to get my head around. I know I’m in danger of wanging on about it, but I’ll say it again: The Young Ones takes up precisely fourteen weeks of my life, but looms over everything else I ever do in a very disproportionate way.

It’s not that I don’t like it – I’m incredibly proud of it, and of my part in it – but it takes up too much space. I’ve been asked so many questions about it, and given so many answers, that I’ve probably talked about it for more than fourteen weeks.

Anyone talking about something for longer than they spend making it is either a) making stuff up, or b) nuts.

I might be both.

The Young Ones is also a cult, and this is another problem, because its devoted fans have a very fixed idea of what the programme is, why it’s brilliant, and what everyone should think about it.

Cults are weird. I know this from being in the cult of The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band. It’s like a secret society. We don’t have masonic handshakes but we have the ability to drop small sentences into the conversation if we suspect another member is in the room.

‘Hey, you have the same trouble with your trousers as I do,’ we might say, or ‘Yes, brr, it is a bit chilly.’ And these phrases might alert the other follower, and we’ll smile at each other, move to a corner, and begin to reminisce.

When I say reminisce I mean repeat wholesale.

I once played Captain Hook in panto in Canterbury and there’s a tradition that the Archbishop always comes to a performance and meets the cast afterwards. As a devout atheist I wasn’t particularly bothered, and was perhaps looking a bit unconvinced as Rowan Williams came down the line. He was being introduced to each member of the cast by our producer but as he reached me he jumped in before the introduction and said: ‘“And looking very relaxed . . .” Adrian Edmondson as Captain Hook.’ The first phrase being a line from ‘The Intro and the Outro’; he knew; we immediately shared a bond; I fell in love with him; we chatted Bonzos, and could easily have gone on all night if Smee and the rest of the pirates hadn’t been waiting so impatiently.

I’m aware there’s a society like this for The Young Ones but I’m not a member of it. People often quote a bit of the show at me, they’ll offer me lines of dialogue, like feed-lines, and expect me to come in with the famous rejoinder – a line that I said in the programme forty years ago. But I haven’t watched it since it was first on TV, and I always disappoint by not knowing the answer. Every Young Ones fan I meet knows the programme better than I do.

Why don’t you watch it?

Because I don’t watch repeats of any of the shows I’ve made. I watch them first time out and then I’m done.

Why?

Because it just seems a weird thing to do. It’s so backward-looking. I’d feel like Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard sadly watching her past glories, with the obvious insinuation that there will be no more. Well, I’m still of the mind that my best is yet to come.

Ha ha ha ha ha!

It’s true.

Ha ha ha.

I’m still looking forward!

Ha . . .

Shut up, and let me tell you what I know about The Young Ones.

The programme is born in the crossfire between the birth of The Comic Strip Presents on Channel 4 and the BBC trying to persuade the same group of people to work for them. The BBC are very worried about losing young viewers to the new channel. It’s also a tussle between the Comic Strip’s leader, Pete, and The Young Ones chief instigator, Rik. There’s no animosity between the two, and indeed they end up living half a mile from each other in Devon, but there’s a definite . . . jostling.

Nigel and I are happy to go along with both. We’re going to be on telly. Twice.

Another bit of grit in the oyster is that The Young Ones contains at least two characters that already exist before writing begins, maybe even all four: Rik’s character, Rick the Poet, has been his solo act for a couple of years; Nigel’s character, Neil the Hippy, has been in existence even longer; Vyvyan the Punk is basically a version of Sir Adrian Dangerous, or is that just my inability to create a new character? Either way, I’m definitely hired as the berserker, a role I’ve been playing for a while; and Mike the Cool Person is very similar to a style and presence of character Pete Richardson plays in his double act with Nigel, and the original intention is that Pete will play him. Pete’s very cool, I mean for God’s sake – sometimes he wears his sunglasses indoors!

However . . .

The Young Ones producer, Paul Jackson, is cut from the same sort of cloth as Pete, in that they both like to be in charge – but there’s an antipathy between them that comes from somewhere else.

Paul’s another red-brick alumnus – Exeter – and he joined the BBC ten years before The Young Ones. He’s worked his way up from assistant floor manager to producer and comes to us having just produced the last two series of The Two Ronnies. He’s very good at his job, and he’s genuine in his desire to produce something more anarchic than The Two Ronnies – not just because the BBC wants to keep young audiences on side, but because it’s his sense of humour and he likes the ‘danger’ of The Young Ones. He’s very enthusiastic about it – but he’s definitely attached to the mainstream when we meet him, like everyone at the BBC he’s a part of the ‘corporation’, and I think Pete views this with suspicion.

And to be honest Pete’s just not a ‘telly’ person. He’s not at home in the world of multi-camera sitcom. He likes film.

In the early days of The Comic Strip the Monty Python producer John Goldstone lends us a basement room in his suite of offices in Soho. There’s a large U-matic video machine in there along with John’s film library, and instead of writing we spend most of our time watching John Waters’ early films, like Pink Flamingos and Female Trouble. They all star Divine and a little repertory company of the same actors – a very similar concept to The Comic Strip Presents. This is Pete’s world.

So Pete and Paul are from two different wings of comedy, in the same way that the RAF and the navy are two different wings of the armed forces. They might have the same objective, but they’re coming at it from different angles, and the upshot is that Pete withdraws from The Young Ones.

Does he withdraw? Or is he pushed? I think there are ultimatums on both sides. I’m not involved in the fracas because, along with Nigel, I’m simply hired as an actor. It’s the first time in my career as an accidental comedian that I’m not involved on the writing side. Not that I feel too excluded, because I’m creating ‘Bad News Tour’ for The Comic Strip at the time, but it’s the reason my involvement with the show is so short.

The Young Ones is written by Ben Elton, Rik and his then girlfriend Lise Mayer. I know from personal experience that writing with more than two people in the room can be difficult. At the time Ben’s already a proven stand-up comic and writer with more than ten plays to his name; Rik is a practising comic genius, but has only created stuff through improvisation up to this point; and Lise is new to the game. They end up writing two separate versions of each episode, Ben on his own, Rik and Lise together, and then squash the two scripts together, but when I see the draft for the pilot it’s mostly in Ben’s scribbly handwriting.

There’s also some kind of struggle between Ben, Rik, Lise and Paul as to who should replace Pete. Ben himself is in the running for a while, as I think is Chris Ellis from 20th Century Coyote days, but these are shenanigans I’m not party to. In the end they hold auditions and Chris Ryan, who’s being hysterically funny in the Dario Fo farce Can’t Pay, Won’t Pay in the West End, gets the part.

In the long run Chris is not treated well by the programme makers, the press or the general public. Once Pete removes himself from the equation, the three writers struggle to agree on what Mike the Cool Person is, the writing for him is generally quite confused, and the character becomes slightly neglected. There’s a scene in one episode where we all come downstairs playing each other’s characters, Nigel is Rick, Rik is Vyv, Chris is Neil and I’m playing Mike, and it’s one of the most difficult things I ever do – it’s hard to get a handle on this character from what’s on the page. Chris’s comic skills are without question – he goes on to create the brilliant Dave Hedgehog in Bottom, and Marshall, Edina’s ex-husband, in Absolutely Fabulous.

He’s also one of the funniest impressionists I’ve ever heard – he does impressions within impressions: he’ll do the American crooner Andy Williams being Sid Vicious, or Orson Welles being Ken Dodd. Some of my favourite memories of making the programme are doing the location filming in Bristol and spending the evenings in restaurants and pubs laughing at Chris.

It’s difficult to appreciate now because we’ve all seen it, and because so many other programmes ‘pay homage’ to it, and because in the world of TV trailers the word ‘revolution’ has become just another marketing term – but The Young Ones is truly different.

It’s couched in the familiar language of all the television that’s gone before: multi-camera, sitcom set, live audience. It uses the same basic grammar as Terry & June, and we’ve already had scatological leaps in Monty Python, and Spike Milligan breaking the fourth wall at the end of every sketch in the Q series.

But what no other comedy show has had before is this:

1. Four completely bloody horrible unsympathetic main characters: venal, selfish, irresponsible, violent, petty and insanitary. Rik and I have a competition before every show to see who can get the most disgusting spots on his face, much to the chagrin of our make-up artist Viv Riley, who yearns to work on costume drama and do ‘pretty ringlets’. There’s never been a sitcom before where all the main characters are meant to be so unlikeable. We’re used to going ‘ahh’ at Felicity Kendal in The Good Life. We love Pike in Dad’s Army and want to take him home. We’re on Manuel’s side in Fawlty Towers.

2. For a lot of young people it’s the first sitcom they can see themselves reflected in. Despite the characters being so nasty they’re completely relatable in a way that many sitcom characters aren’t, even the good ones. I love Steptoe & Son but I don’t know anyone like Harold or Albert. I love Hancock’s Half Hour but I don’t know a Tony or a Sid. But if you’ve been to school or university you will know a Rick, a Vyv, a Neil or a Mike. In fact the chances are you probably are one, or an amalgam of two or more of them. Their meanness, their pettiness, their going behind each other’s backs – that’s you, that is.

3. It talks about things no other comedy programme has before: periods (no one has seen a tampon on telly before), masturbation, Thatcher, bogies. It looks surreal on the surface but it’s about grubby realities. There’s a level of crud and filth that goes way beyond anything in Steptoe & Son but it’s totally recognizable to anyone who’s lived in a student house. And there’s a political attitude that’s also quite novel. If not exactly red, it’s very red-brick. We are Scumbag College – which is where most people go.

4. It has a level of slapstick and violent stunts that haven’t been seen since the days of Laurel & Hardy and Buster Keaton. I make my first proper entrance into the public consciousness crashing through the wall into The Young Ones kitchen. In the same episode I bite a brick which explodes – it’s made of Ryvita biscuits which makes it sound harmless, but it contains a small explosive device that’s detonated by the offscreen SFX (Special Effects) team. The healthy wholegrain crispbread may be low in saturated fat but it cuts me quite badly and leaves me deaf for a week, but I don’t complain because it’s a great gag. And I’m a berserker. The SFX team love me because I make it clear from day one that I’m never going to sue. When they ‘slightly’ overcharge the cooker with explosives it blows up and the flames lick all around the set – the heat is so incredible that the plastic clock on the opposite wall melts. You don’t get this kind of thing on Don’t Wait Up or To the Manor Born. SFX fill their boots when we arrive. One of the joys of the whole process is going to the SFX department – a kind of Nissen hut on the outer reaches of the BBC compound – like in those war films where they go to see what ‘specials’ the mad boffins might have come up with to fool Jerry. There’s an array of Heath Robinson machines: gas tanks firing dirty laundry out of washing machines – it comes out so fast in the actual episode that Rik cuts his eye; explosions, rubber cricket bats, frying pans, breakable bottles and plates; giant sandwiches and eclairs; people working out how to get a wrecking ball through the set wall or blow up a bus. Terry & June never ask for this kind of thing, so they absolutely adore us, and when it comes to me kicking my own head down the railway track – obviously I can’t be in the same shot with my own head because they’ve dug a hole, stuck me in it, and backfilled me with ballast – so the SFX designer Dave Barton steps in as the headless body because he has the unique ability to lower his head to such an extent that if you look at him from behind he looks like he has no head. And because he’s SFX-trained he manages to keep the blood spurting out of his own open wound at the same time. Hero. Later, when we do the Dangerous Brothers on Channel 4 the SFX team aren’t quite as knowledgeable. There’s a sketch in which we’re doing an impression of The Towering Inferno – the SFX people smear my lower legs with glue and tell me the flames will come up to my waist. I’m wearing fireproof long johns and they say they’ll stand by with extinguishers. I’m conscious that my dialogue is something like ‘Help! Help! I’m on fire!’ And I don’t want them to misinterpret this for an actual cry for help so we agree on a codeword that I will shout if things get too much. We start recording, Rik sets fire to me, and the flames immediately engulf my entire body, burning my eyebrows off and scorching the inside of my throat. In the surprise of this unanticipated scale of conflagration I immediately forget the codeword. ‘Help! Help!’ I cry. ‘No, really – I’m properly on fire!’ Everyone watching is laughing, thinking that this is brilliant, that I’m improvising, that I’m perfectly OK because I haven’t uttered the codeword. I bluster on, genuinely crying out for help as they continue pissing themselves and it’s only Rik – who notices something different in the frequency of my voice – that calls for them to put me out. Thanks, you bastard, though you could have spotted it a bit sooner.

5. There’s a live band every week. Admittedly this is partly a lucky accident because it’s a requirement of being commissioned by the Variety Department rather than the Comedy Department. But Paul takes it to the Variety Department because they have bigger budgets, which means more special effects and two days in the studio every week – one to pre-record, and one in front of a live audience. And we love our audience. Paul’s mantra is ‘If you’ve got a big joke do it in front of an audience.’ Which is why Rik and I are dropped 20 foot from above the studio into the kitchen on a double bed. There is some protection – the bed is basically a disguised tray holding collapsible cardboard boxes – but in reality we’re doing the work of proper stuntmen. In front of a live audience. If you look closely you can see how winded and shocked we are as we struggle out of the crushed boxes and continue fighting.

6. It’s full of ideas. Rammed in fact. John Chapman, a successful writer of Whitehall farces, was one of the writers of the seventies sitcom Happy Ever After, starring Terry Scott and June Whitfield. I have to make it clear that I love and admire Terry Scott and June Whitfield. However, John Chapman’s on record as saying the show had ‘run out of ideas’ by 1979 and had to come to an end. But the executives were so keen to continue the show they simply changed the name to Terry & June and employed new writers. Essentially between 1979 and 1987 they made nine series of a show which had ‘run out of ideas’. Despite the odd jewel like Fawlty Towers and Yes Minister this was the state of a lot of sitcoms at the time. Compare the plot of the Terry & June episode ‘New Doors for Old’, in which Terry and June buy a new front door only to discover it’s two inches too short but they’ve already thrown the old door away – that’s the entire plot – with the plot of The Young Ones episode ‘Oil’, in which: Buddy Holly is found singing in the attic; Vyv sets fire to Rick’s bed; a genie appears from the kettle; Neil gets eight arms; Mike has to dispose of a dead body; the oven explodes; two men are living on a raft in some kind of weird hallucination; Mike opens a Roller Disco in Rick’s bedroom; Neil finds a moose’s head in his bed; Vyv discovers oil in the cellar; there’s a parody of Upstairs Downstairs in the broom cupboard; Neil sneezes so violently the broom cupboard explodes; a dictatorship emerges with Mike as El Presidente and Vyv as his brutal police force; there’s a prescient gag about Arab potentates chopping up people they don’t like; Neil accidentally puts a pickaxe through Vyv’s head; and there’s a failed revolution which includes a very badly attended benefit concert.

You’ve got a very good memory for someone who never watches the programme.

Tough luck, buster! I had my fingers crossed behind my back all along!

No, in truth, in trying to explain my point about how crammed full of ideas it was, I had to watch an episode – I reclined on my chaise longue like Norma Desmond and had my eccentric butler lace up the old projector.

I was surprised by how good a lot of it still looked, though some bits are just as dreadful as I remember – the two men on the raft in the cellar. What’s that about? It was deadly boring at the time but now it looks insane, and not in a ‘zany’ funny way. It looks plain wrong, like it’s from another show. A really crap show. I was so mesmerized by the horror of it that I had to go back and time it – it’s over two minutes long. And I counted the jokes – none.

I was never particularly keen on all the puppets either. For all the ‘anything can happen’ vibe I’d have been happier with just the four boys, that’s where all the best jokes are.

But watching it also reminded me of the sheer exhilaration of studio nights, and the joy of playing to a live audience.

There’s one laugh I can hear that crops up all the time, it’s a constant at every show we do, including every studio night for Bottom, and that’s Rik’s brother Ant. He’s such a brilliant supporter of all our endeavours. He’s not a plant, his laugh is genuine, but he’s always slightly ahead of everyone else, and he’s infectious. Every audience needs a ‘seed’ laugher – someone who shows them it’s all right to laugh – and Ant is our man. His laugh is just a beautiful and innocent expression of joy and delight, and he’s what we call a ‘jazzer’ in that he’s the first to pick up on the more esoteric material. I think it’s a word Rik and I invent, or at least a meaning we invent – where in jazz you might have an aficionado who recognizes all the subtle variations and changes in pitch and tempo, we use it in our world to mean someone who recognizes all the jokes, not just the obvious ones. If there’s a joke we struggle over when writing Bottom, and worry about keeping it in, if Ant laughs then we know we were right.

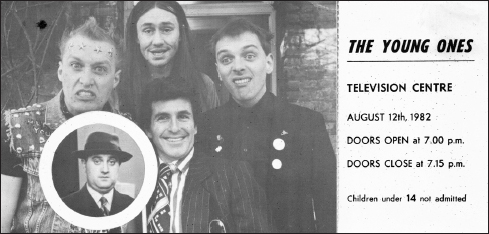

Watching the episode I’m also reminded of the pressure of studio night, the worry of getting it done in time. We’ll have recorded some bits the day before – the boring bloody raft, the dull puppets etc. – but the second day is camera rehearsals until 6 p.m., then audience in at 7 p.m., and start recording at 7.30. It’s basically a theatre show with cameras, but there’re lots of very technical elements that mean a lot of stops and starts, and multiple takes to make sure we get it right. And we have to get it done by 10.00, a) because the audience start to get really bored, and b) because after 10.00 the whole caboodle swings into expensive overtime and Paul starts breaking pencils, throwing things at the monitors, and shouting at everyone.

Paul is a lovely man and he’s our true champion – he’s the man who gets The Young Ones, Filthy Rich & Catflap, the Dangerous Brothers and Bottom on to the telly – but he can also be a very angry man. There’s a depiction of a comically angry director in an episode of Filthy Rich & Catflap played by Chris Barrie, which is basically an impression of Paul at five to ten on a studio night.

Ed Bye, who is the assistant floor manager on the first series, our floor manager on the second, and who will go on to direct Bottom, is comically diplomatic through it all. Paul will be in the control room, Ed will be on the studio floor relaying Paul’s messages. Ed’s a very affable and courteous man, and the more apoplectic Paul becomes, the more Ed manages to exude an air of absolute calm. The BBC headphones of the era leak very badly and we’ll be able to hear Paul ranting and raving, effing and jeffing at the top of his voice, and when the tirade finally ends Ed will say: ‘Paul wonders if you wouldn’t mind, very kindly, moving a little to the left.’ Or: ‘Paul thinks we should perhaps try it the way we rehearsed it.’

Ed’s also in charge of collecting the money after the post-show group meals: every show is like a first night and a last night rolled into one, and is therefore an excuse to party big time. The release of nervous energy is off the scale as we inveigle our way into the BBC Club at TV Centre to get a few pints in before going to one of the Indian restaurants on Westbourne Grove. It’ll be a huge party – the cast plus partners and family, the band and hangers-on, people from production – there’s generally thirty to forty people all fairly shit-faced and ordering freely. It’s Ed’s job at the end of the meal to check the bill and start collecting . . . it’s sometimes funnier than the show.

‘Er, Mr Sensible,’ he’ll say as Captain Sensible walks up and down on the table tops, handing out Tony Benn’s latest pamphlet. ‘I think you had the lamb bhuna and . . . four pints, does that sound right?’ ‘Ah, Lemmy from Motörhead, you’re back from the toilets, good – there’s just the little matter of the bill . . .’

‘Five Go Mad in Dorset’, the first episode of The Comic Strip Presents, goes out on the first night of Channel 4 – 2 November 1982. Culture Club are top of the charts with ‘Do You Really Want to Hurt Me?’ Turns out the BBC do want to hurt us because the first episode of The Young Ones goes out exactly one week later. We think we’re lucky to get two very different comedy products onto the telly in the same year but the broadcasters obviously see it as a cut-throat competition. We’re in competition with ourselves!

We make twelve episodes and that’s it. Rik’s very impressed by John Cleese only making twelve episodes of Fawlty Towers and thinks if we copy him The Young Ones will be just as iconic. And Rik’s very keen to be a legend. Besides, the writing room has collapsed: Rik and Lise split up, Rik and Ben start to write Filthy Rich & Catflap together, but in the end Rik leaves all the writing duties to Ben.

The success of The Young Ones changes the lives of everyone involved, but changes Rik more than anyone else. He loses the uncomplicated charm of his student days and becomes much more complicatoratory, as George W. Bush might say. He falls in love with his fame.

Just going down the street with him becomes a trial, because he walks around as if every passer-by is a future biographer in search of an amusing anecdote that will prove how off the wall he is. He gurns at people until they recognize him, eyes swivelling to attract attention, then he’ll do something ‘outrageous’ like pretend to pick his nose and wipe the bogie on their coats.

This excites some passers-by who will then ask for an autograph, and it will take for ever to find paper and pen, and if they are female it might entail a hug, a kiss, and a squeeze.

I alluded earlier to a shared idea we once had of what happiness was: being in a cosy boozer with a pool table and a jukebox full of seventies hits. It feels like Rik has now re-entered this dream as a jack-the-lad, flashy pools winner.

It’s exhausting, and the weird thing is that he’s completely aware of how ludicrous he’s being. Once we get back into a private space he’ll become old Rik again, making jokes about how vain and preening he is, and about the very people he’s just been trying to impress, who he calls ‘the ghastly ordinaries’.

Of course I’m lying when I say The Young Ones only takes up fourteen weeks of my life because in 1986 we make the ‘Living Doll’ single with Cliff Richard for Comic Relief. It’s a day to record, about two minutes to make the rather shambolic video in a dreary park in north London, and three nights doing the Comic Relief live show. So make that fifteen weeks. It stays at number one in the UK for three weeks, keeping Bowie’s ‘Absolute Beginners’ off the top spot, which is a travesty.